History of the ships "la Boscaina" and "la Ferrara"

The discovery of the Mortella wrecks immediately raised the question of their origin, their identity and the historical events that led to their tragic fate in Corsica. These questions led to the organisation of documentary research in French, Italian and, later, Spanish archives and libraries, which resulted in the study of several cases of shipwrecks that occurred in 1526, 1527 and 1555 in the Bay of Saint-Florent.

In order to correctly interpret the three historical events described, it is necessary to situate them in the complex Mediterranean geopolitical context of their time. This context was particularly marked by the rivalries between France and Spain, which were expressed through the wars between Francis I and Charles V in Italy. The first half of the 16th century saw a succession of eleven wars, beginning with Charles VIII’s attempt in 1497 to recover the Kingdom of Naples – which he considered part of his Angevin heritage – annexed in 1447 by Aragon, and culminating in 1559 – after more than 60 years of wars that ravaged the whole of Europe – with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis. As we can see, whatever the proposed date, it is to this tumultuous political context that the Mortella shipwrecks are linked.

At a time when the dating of the furniture of the Mortella shipwrecks is rapidly moving towards the 16th century, it was an event in 1555 that initially attracted attention and led to the first hypothesis for the identification of these wrecks, given that they could correspond to two Spanish ships sunk in December 1555 by Antoine Escalin, Baron Paulin de la Garde, general of the galleys of the King of France. The contemporary Corsican chronicler Marc-Antonio Ceccaldi (1520-1560) recounts the event: Baron de la Garde was returning from Civitavecchia on a diplomatic mission with a fleet of 14 galleys. A violent storm forced him to take refuge in the bay of Saint-Florent. At the same time, a fleet of 11 Spanish ships was heading for Genoa. Caught in the storm, the Spaniards also took refuge in the Bay of Saint-Florent.

Thereafter, with France and Spain at war, as we have said, confrontation was inevitable. However, the Spanish ships arrived in port in a dispersed formation, while the French fleet was concentrated there. It was in these circumstances that two ships of the Spanish fleet commanded by Alonso Pimentel, admiral and friend of Charles V, were captured and sunk. In their attempt to escape, two of the Spanish ships broke on the reefs and were wrecked. This event is also recounted with some variations in two documents that we have located in the archives of Simancas in the archives of Simancas (AGS, Valladolid, Spain). These are two letters dated 21 December 1555 and 2 March 1556 from the Spanish ambassador in Genoa, Gómez Suárez de Figueroa, to Juana of Austria.

This hypothesis is compatible with the Italian origins revealed by the study of the wreck, also taking into account the geopolitical context of the 16th century, which enshrines the alliance between Spain and the Republic of Genoa. However, the dendrochronological dating of the Mortella 3 wreck suggests that the shipwrecks took place around the first third of the 16th century; it seems unlikely that the Mortella ships were wrecked in 1555 after 35 years at sea, or even 30 years if we take into account a few years between the drying of the wood and the construction of the vessel.

Although this duration is not impossible, it is more than double the average duration of a large vessel in the Mediterranean in the 16th century. For this reason, documentary research was pursued in search of a maritime episode in the Bay of Saint-Florent with a closer chronological coincidence. This led to the identification of several texts that relate other shipwrecks earlier in time, first in 1526 and then in 1527, the latter episode seeming – today – the most likely to explain the presence of the remains of the Mortella.

Two Italian authors – Paolo Giovio and Agustino Giustiniani – recounted the historical event that originated the shipwrecks:

En el transcurso de 1527, la ciudad de [Génova], entonces bajo el dogado de Antiniotto Adorno, estaba sumida en una terrible hambruna, el grano se había agotado hasta tal punto que se racionaba el pan….. Se armaron cuatro lanzaderas con el apoyo de barcos de Sicilia… para transportar grano a la ciudad, entre ellas las lanzaderas La Ferrara y La Boscaina de Rapallo, que fueron perseguidas por las galeras francesas en el golfo de Saint-Florent, en Córcega, y se vieron obligadas a desembarcar por falta de viento. Las tripulaciones se salvaron, pero los barcos fueron incendiados…

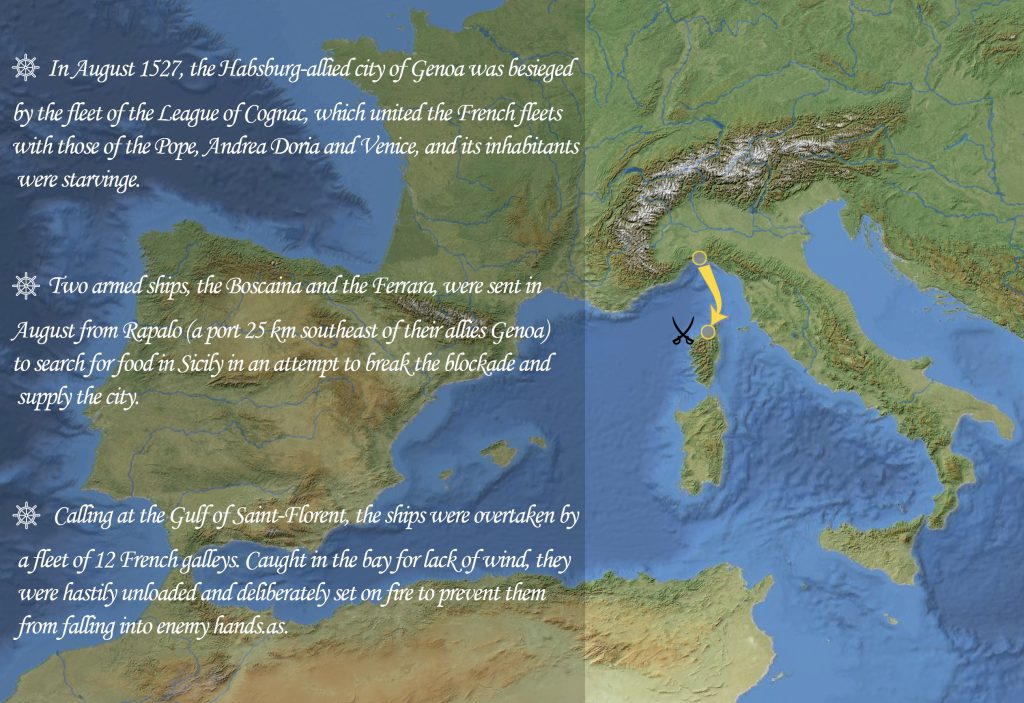

In August 1527, the Habsburg-allied city of Genoa was besieged by the fleet of the League of Cognac, which united the French fleets with those of the Pope, Andrea Doria and Venice, and its inhabitants were starving. Two armed ships, the Boscaina and the Ferrara, were sent in August from Rapalo (a port 25 km southeast of their allies Genoa) to search for food in Sicily in an attempt to break the blockade and supply the city. Calling at the Gulf of Saint-Florent, the ships were overtaken by a fleet of 12 French galleys. Caught in the bay for lack of wind, they were hastily unloaded and deliberately set on fire to prevent them from falling into enemy hands.

Giustiniani’s text provides a series of data which, when analysed, suggest that the shipwrecks of 1527 are the ones that best match the archaeological facts with the historical ones: two Genoese ocean-going vessels destined to transport wheat were in danger of being overtaken by a fleet of French galleys that had set off in pursuit of them due to a lack of wind. The option chosen was to unload the ships in haste and – in these circumstances – it is conceivable that there was not enough time to unload the anchors and cannons. According to Giustiniani’s version, the ships were then deliberately set on fire to prevent them from falling into enemy hands.

This shipwreck highlights a complex political situation that reveals the division of Italian cities that this Franco-Spanish rivalry was creating: on the one hand, we see Venice united with the Vatican on the French side, rising up against Genoa. On the other hand, we see how Genoa’s alliance with Spain and that of the Genoese general Andrea Doria with France led to the latter’s ruthless war against his own home city. A study of the texts shows that the shipwrecks of the navi della Mortella are a direct consequence of this thorny political situation.